Last month, we learned about Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) and laminitis in Timber, a middle-aged gelding. This month we are going to focus on a similar metabolic disease seen typically in older horses. This is the story of Spud, a 21-year-old Appendix Quarter Horse gelding, used as a children’s light riding horse.

I met Spud in the spring of 2016 shortly after his family had moved from Idaho to Northern Arizona. Spud and his pasture-mate, a 9-year-old Mustang mare, had made the journey without incident and they were both settling in well. Spud’s owner had made an appointment for routine vaccinations and a dental exam.

Spud’s History

It had been a couple of years since Spud’s last dental float and the owner had seen wads of chewed hay near his feeder and noticed an intermittent foul odor from his mouth over the last few months. The owner had also seen a slow decline over the last year in his willingness to work under saddle. He lacked “spunk” and his youth rider struggled to get Spud to do much more than a slow jog. The owner attributed this to his advancing age. A month before moving to Arizona, Spud became acutely lame in the RF leg. The veterinarian in Idaho found a hoof abscess and drained it promptly to relieve the pressure. Spud made a full recovery from the abscess. The owner remembered the veterinarian in Idaho discussing Cushing’s disease with her at that time but no further investigation had been sought out by the owner.

Physical Exam

On Spud’s physical exam in the spring of 2016, he was presented to me with a long, thick winter hair coat with minimal shedding. This contrasted with his pasture-mate, who was nearly completely shed out, with an actively shedding coat. The owner reported Spud had been holding on to his winter hair coat longer than the other horse for the last three years. However, his coat would be completely shed out by late summer each year. Spud’s attitude was somewhat dull, but he would perk up when taken away from his pasture-mate. Spud’s body condition score was difficult to gauge due to a ribby appearance, yet significant fat pads over his croup/tail head and neck. When the owner was questioned about his overall body condition and weight, she reported that he had lost weight over the last 6 months and had continued to look ribby since the move despite a good appetite. Spud’s temperature and heart rate were normal. A low-grade heart murmur was heard when listening to his heart with a stethoscope. This murmur, based on its timing and intensity, was determined to be benign in a geriatric horse. Spud’s respiratory rate was mildly elevated. No specific cause for this was determined on his physical exam; it was attributed to the warm ambient temperature and his thick winter hair coat. Spud’s front hooves appeared overgrown with excessive heel growth and a slightly dished appearance on his toe. He walked normally on soft ground but was hesitant to stride out normally (short, choppy gait) on rocky footing and hard ground. He was mildly sore when turning in both directions.

Oral exam

Since the owner was concerned about Spud’s ability to chew normally, he was sedated for an oral exam. A dental speculum was placed to enable good visualization of his oral cavity. The oral exam revealed a wave mouth, which is very common in older horses. The arcades in the horse are usually flat with a slight angle on the occlusal (chewing) surface. In a horse with a wave mouth, the premolars and molars have varying heights, often mimicking an ocean wave. The wave is caused by slower tooth eruption rates in some teeth and normal eruption rates in other teeth. This finding was most likely the reason for the wads of hay the owner was seeing around the feeder, as Spud was unable to chew the hay normally. He also had a few areas of gingivitis, where food likely packed between his teeth and the gum. This most likely was the cause of the foul odor the owner noticed intermittently. A dental equilibration (laymen term: float) was performed, but due to the extensive wave, only a partial equilibration was completed to reduce the wave. It was recommended to the owner to repeat the equilibration in 4-6 months to further address the wave.

After the oral exam and routine vaccinations, Cushing’s disease was discussed with the owner, due to some classic clinical signs of the disease in Spud. The owner declined testing and treatment due to financial reasons. Laminitis (founder) was discussed with the owner due to his soreness and abnormal hoof conformation, but the owner declined further work-up.

Laminitis

Spud was seen 5 months later for acute soreness in his front legs. In the time since the last visit, the youth rider had been unable to ride him due to ongoing soreness and unwillingness to work. He had been housed on a 2-acre pasture with native flora and rocky footing. Spud was very sore to walking on hard footing with a short, shuffling gait and resisted turning in both directions. He was sore to hoof testers at the toe in his front hooves, indicating soreness in this region. Laminitis was suspected due to the previous exam findings, ongoing lameness, and now additional soreness.

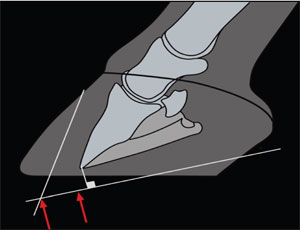

Radiographs (x-rays) were taken of his front hooves. Findings included a long toe and high heel with evidence of coffin (pedal) bone rotation in both front hooves. Based on these films, laminitis with significant rotation of the coffin bone was diagnosed. It was recommended to confine Spud to a small area with soft bedding to encourage him to lay down. Phenylbutazone (bute, an anti-inflammatory/anti-pain drug) was initiated to help reduce pain and inflammation in his hooves. Although it was highly recommended, the owner was unable to perform ice therapy on his hooves, to further reduce inflammation, due to time-constraints. Treatment for the suspect Cushing’s disease (pergolide, Prascend®) was initiated without diagnostic testing for the disease due to financial reasons.

Over the course of the next week, Spud’s comfort level waxed and waned. He appeared to only partially respond to the bute therapy so additional anti-inflammatories were tried with little change. After 1 week, a modest amount of toe and heel were removed by the farrier and Styrofoam pads were placed on his feet to provide soft support to the bottom of his hoof. Spud’s pain continued despite treatment. Repeat radiographs of his hooves were performed 1.5 weeks after the initial set, which showed additional rotation of the coffin bone. A frank conversation about Spud’s poor quality of life and unrelenting pain despite therapy was discussed with the owner. She agreed and requested euthanasia.

Posterior Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID)

Equine Cushing’s disease is better known as Posterior Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID) in the veterinary community. It is commonly seen in older (>15 years old) horses and ponies of all breeds but can occur in younger animals. It has been documented worldwide and has even been reported in other equid species, such as the Persian onager. The disease is caused by a benign pituitary tumor (adenoma) in the brain. Adenomas, in general, don’t cause problems, except when they become large and disturb surrounding structures or when they disrupt the delicate balance in the body by secreting excessive hormones.

In PPID the abnormal cells of the adenoma feedback on the adrenal gland near the kidney, causing the adrenal gland to release “stress” hormones, such as cortisol. Because of this, the PPID horse is always in a state of metabolic “stress.” This causes disruption in many different body systems, as demonstrated by some of the common clinical signs seen:

- Hirsutism (long, thick hair coat), abnormal shedding patterns, delayed shedding

- Excessive drinking/thirst and subsequent excessive urination

- Changes in body shape (abnormal fat distribution on crest of neck, thorax, and tail head; pot-belly; ribby; muscle wasting)

- Abnormal sweating or problems maintaining body temperature

- Prone to infections (hoof abscess, skin disease, dental disease, as well as common injuries (cuts and scrapes, eye ulcers) taking longer to heal than normal)

- Laminitis

The clinical and molecular research on PPID is very active, and new recommendations on how to diagnose, treat, and manage the disease changes frequently as we learn more. Diagnosis is sometimes made on clinical signs alone, especially if the disease is advanced. Veterinarians are making a good effort to diagnose this disease early, before the horse’s quality of life has deteriorated. Testing to diagnose PPID is relatively simple, requiring one or two blood samples to send to a laboratory that specializes in horse endocrine testing. Treatment of PPID revolves around reducing the amount of excessive “stress” hormones by providing an artificial feedback system to the pituitary. The drug most commonly used is pergolide mesylate (Prascend®), which was originally developed in the 1980’s to treat Parkinson’s disease in humans. Unfortunately, it had too many side-effects to make it safe for human use. Luckily for horses, the drug is very safe and only has a few side-effects that can be managed easily. Most horses respond well to pergolide therapy, but there are other drugs that can be added or tried if the response isn’t adequate. Management of PPID, in addition to pergolide, revolves around management of an older horse. Routine vaccinations, fecal exams to check for parasites, regular farrier visits, regular dental exams, good nutrition, and exercise are important for older horses, especially those diagnosed with PPID. If the horse has a thick hair coat when the pergolide therapy is started, the owner may need to clip the hair off to provide some relief to the animal, especially in warmer climates. Response to treatment of PPID is based on clinical signs. The animal should begin to look more normal within 6-12 months.

So, what went wrong in Spud’s case?

On initial presentation in the spring of 2016, Spud’s history and clinical examination findings indicated ongoing PPID with suspect low-grade laminitis already occurring. Some of the red flags included: history of abnormal shedding for multiple years, history of signs that indicated chronic footsoreness, history of a hoof abscess, poor foot confirmation indicating chronic laminitis, abnormal fat distribution throughout his body, and dental disease. In medicine, it is hard to predict what would have happened if treatment of the metabolic disease would have been initiated earlier. But most likely, if pergolide therapy would have been administered when he first started showing signs of the disease (3 years earlier), the drug would have controlled the PPID and the laminitis bouts would have been prevented.

When presented with a horse with laminitis, the veterinarian must think about the bigger picture of what is causing the laminitis, since it typically does not occur by itself. In Spud’s case, PPID was most likely the primary metabolic disease that caused secondary laminitis. In Timber’s case, a similar metabolic disease, Equine Metabolic Syndrome, caused the secondary laminitis. Another cause of laminitis is called support-limb laminitis, where the horse suffers a severe injury (fracture, severed ligament or tendon) in one leg and is forced to weight-bear more on the opposite leg. The increased strain and stress on the “good” leg can cause laminitis to occur. Barbaro, the famous racehorse who won the 2006 Kentucky Derby, suffered from support-limb laminitis after a catastrophic fracture was repaired, which ultimately lead to his euthanasia. Supportive treatment is recommended for the laminitis in all cases, but it is imperative to address the primary problem to have a successful outcome.

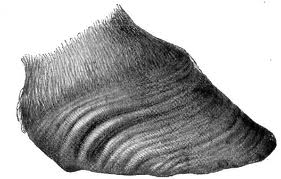

Abnormal foot conformation (long, dished toe and high heel) is a classic finding in horses with chronic laminitis. The heel grows faster than the toe, due to poor circulation within the hoof. This results in laminitic/founder rings, which gives the hoof a distorted appearance. Farriers are often concerned about trimming the hoof too much because they often have bruising evident on the sole and stretching of the white line (distinct line near the edge of the hoof connecting the sole to the hoof wall). Radiographs help the farrier improve the balance of the hoof because they can see where the coffin bone is in relation to the hoof wall. It is a myth that farriers or veterinarians can “derotate” the coffin bone within the hoof capsule. What often occurs over time is the farrier removes excessive toe/heel and matches the amount of rotation that has already occurred. Proper farrier care is so critical in horses suffering from laminitis.

Hopefully, this article provided you with useful information about PPID and laminitis. My hope is Spud’s story can help educate horse owners to intervene early in the course of the disease and help prevent the secondary problems that are likely to occur. Have a good relationship with your farrier and your veterinarian and ask questions if you feel something is not quite right. You know your horse better than anybody else!

Prescott Animal Hospital Equine Center

What's Next

Call us or schedule an

appointment online.Meet with a doctor for

an initial exam.Put a plan together for

your pet.